Where We Work

See our interactive map

Tracy Kobukindo is a registered nurse and advocate in Uganda. She also serves as a Frontline Health Workers Coalition Regional Advisor, helping to guide the Coalition’s advocacy messages and policy recommendations. Photo by Tracy Kobukindo.

Nurse and Advocate Tracy Kobukindo shares her recommendations for policymakers.

Health workers in Uganda are now at the forefront of responding to another serious infectious disease. Last month the country declared an Ebola outbreak, caused by the Sudan species of the virus. There’s no licensed treatment or vaccine for this strain of Ebola yet, and according to the World Health Organization (WHO), the mortality rate is greater than 41%.

COVID-19 has magnified how critical health workers are for emergency response and global health security. Today, they identify people infected with Ebola, ensure they are isolated, and provide early treatment to save as many lives as possible. But for years, Uganda has faced a concerning shortage of health workers. The World Health Organization’s Regional Director for Africa said this shortage contributed to health workers not detecting the virus sooner, as well as its spread. The Minister of Health has urgently requested funding and support for more health workers who can safely contain and halt the outbreak.

David Bryden, director of the Frontline Health Workers Coalition, reached out to Tracy Kobukindo, a nurse and advocate in Uganda, to ask about the current situation for health workers. Tracy is a regional advisor for the Coalition and a manager on the education team at Last Mile Health. She shares how she sees the outbreak impacting health workers and her recommendations for policymakers.

The outbreak was declared on September 20 in Mubende District, and the virus has now been detected in seven other districts, including in Kampala, the bustling capital city.

According to the update from the Ministry of Health this week, we’ve had 131 confirmed cases of Ebola–46 people have died, 49 people have been treated, and 36 people are still receiving treatment. Eighteen health workers have contracted Ebola—while they were providing care to sick patients. So far six health workers have died.

The Ministry of Health said in an update last week that it will be evaluating the efficacy of three candidate vaccines on contacts in the coming weeks. I hope health workers will be prioritized to receive a vaccine once approved.

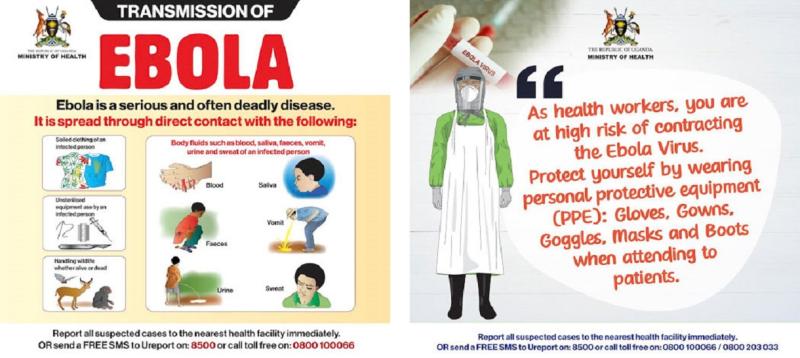

The government has been conducting mass communications campaigns aimed at the public and at health workers. For example, posters and announcements with info about Ebola have been shared on social media, radio, and television with a clear message to immediately report any suspected cases.

Posters shared by the Ministry of Health on social media.

So Ugandans are on high alert and I think have a clear understanding of the signs and symptoms of Ebola. But stigmatization of people and families with Ebola is very high and unfortunately likely discourages some with Ebola symptoms from seeking treatment.

The government has put Mubende and Kassanda Districts–the current epicenters of the outbreak–on lockdown, and has increased military presence to reinforce rules. The government has set up Ebola treatment centers in Mubende and Kampala, and is working to deploy former emergency COVID-19 responders to these centers. But will we have enough supported and protected health workers willing to risk their lives to staff these centers and treat people with Ebola?

The Minister of Health Jane Ruth Aceng has recognized health workers’ selfless service and hard work and is stressing they need to wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and ensure infection prevention and control measures. But I think health workers need more.

Health workers need to know they will be cared for. When COVID-19 hit Uganda, a huge challenge was not having enough PPE for health workers. Now I’m hearing the biggest challenge is health workers are afraid of dying from lack of quality specialized care if they contract Ebola. I’ve talked to several health workers who previously worked with COVID-19 patients, and they said they would not do Ebola.

Health workers are very aware of the high fatality rate and some are not willing to risk their lives this time.

Health workers need to be paid and need for their families to be protected. Back in 2020, the government did massive recruitment of health workers to be deployed as emergency COVID-19 responders under special contract to work in COVID-19 treatment centers. They were supposed to be paid a higher rate, but some health workers have been paid less than their contract stipulated, and many are waiting for their full payment. When COVID-19 was no longer seen as a threat, they were laid off without being paid fully. I’ve heard accounts of some of the emergency responders waiting for up to six months of pay. So these health workers are still demanding money from the government for their previous service, and now they’ve been called back to work on Ebola. Many are not keen to risk their lives again to Ebola, especially without pay or death insurance for their families.

I’ve also heard that health workers in Mubende District have abandoned their posts and normal work stations, worsening the existing shortage of health workers available to detect and treat Ebola patients, but also provide essential health services everyone needs access to.

Health workers need to counter distrust and misinformation that grew during COVID-19. Uganda’s national incident manager for Ebola, Henry Kyobe Bosa, stated this week that health workers here have the huge burden of rebuilding trust—a challenge that can feel immense.

Starting later this week, nurses will lead a mass door-to-door polio vaccination campaign targeting 8.7 million children under five years of age, but the areas with Ebola cases will have to wait. And we have other infectious illnesses to prevent and respond to as they occur. For example, flu/cough remains rampant in small school going children, and Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever has just been confirmed in Amudat, in northern Uganda.

Prioritize implementing pre-existing commitments to support health workers. In Uganda, this includes paying allowances promised to health workers who served as COVID-19 responders. I realize the Ministry of Health has budget constraints but health workers must be prioritized–and paid and protected–so they are retained. The government should increase funding for health and health workforce in the domestic budget.

All countries–and donors too–need to allocate funding for long-term health workforce strengthening to ensure there are enough qualified health workers who are trained, equipped, supervised, adequately paid, and have access to the care, treatments, and vaccines they need, to safely provide care AND respond to the next outbreak. The African Region is facing a shortage of 6.1 million health workers by 2030, and we know this shortage impacts global health security and achieving universal health coverage.

The world expects health workers to risk their safety and lives to provide care during disease outbreaks. Health workers I know are often in low-resourced settings, are overworked, and suffer trauma and shocking events silently. Who will care for the health workers? How will we treat health workers? Where are their voices in this fight?

This conversation was edited by Carol Bales for length and clarity.

This blog post was originally published on the Frontline Health Workers Coalition blog on November 3, 2022. Read it here.

Get the latest updates from the blog and eNews