Where We Work

See our interactive map

Fear and bias get in the way of humanitarian work every day. We're moving forward anyway.

Remember the last time you walked up to a door and pulled on it, only to find you were supposed to push?

I hate that. We all hate that. Especially when it’s a door we’ve been through before, and we should have remembered how it worked, and great, probably everybody saw us.

Unfortunately, our memories are just not very reliable. This is what user experience and game design expert Celia Hodent told us today on the second and final day of SwitchPoint 2018. Good design can overcome some of our deficiencies—if there’s a handle on the door, we’re more likely to pull, a plate and we’re more likely to push.

But it’s tough to truly overcome our cognitive biases, Hodent said. These are the irrational mistakes we make because of the beliefs and preferences buried deep in our brains—even when there’s information right in front of us, proving we’re wrong.

Our cognitive biases lead to ugly stereotypes.

Like when we think our perceptions of reality are better and truer than someone else’s, or how we can spot flaws in someone else in a flash but can’t see them in ourselves. Cognitive biases lead to ugly stereotypes, and to that inherent sympathy we often have for people who remind us of us.

They also make us blind to the bigger picture when we’re too focused on our own objectives. They make us miss things—like when Hodent showed us this video. (It was a little embarrassing how many of the almost 400 people in the audience missed the best part.)

Worse, we didn’t even know we missed it. We’re blind to our own blindness, Hodent said.

But why does any of that matter to global health experts or technologists, or any of the rest of the humanitarians who come here to Saxapahaw, North Carolina, from around the world every year for the SwitchPoint conference?

Because our biases affect every aspect of humanitarian work today. When doctors don’t listen to their clients, because what do they know—that’s a bias. When NGOs see each other as competitors rather than collaborators, even when we know on a rational level that we could make a bigger difference if we joined forces—that’s our bias.

And few things bring our biases to the surface like images of other people. It’s a huge challenge in the field of humanitarian photography.

“There’s a long history of Western photographers using the visual language of photojournalism to perpetuate negative stereotypes of Africa and other parts of the world,” said photojournalist Trevor Snapp today. “Even images that are true can perpetuate untruths. People give money based on images, people go to war based on images.”

So maybe technology can save us, right? What if we start using all this artificial intelligence (AI) we keep reading about to help us make better decisions about how we carry out humanitarian work?

“Well, not necessarily,” Hodent said. “AI picks up our biases and perpetuates them faster and stronger than we do at the individual level.”

Erich Huang of Duke University’s School of Medicine agrees.

“I trained as a surgeon, but I now spend more time coding,” he said. “And coding is just a tool, like a scalpel. I can use it to help a patient, or I can use it to harm a patient.” Algorithms and software can be every bit as racist as people.

So that’s the dark side of humanitarian tech.

“Technology can bring us great things, but it brings us perils too,” Huang said. “We have to think hard about transparency and interpretability in algorithms.”

So that’s the dark side of humanitarian tech.

But today we also saw how solar power is edging out hazardous kerosene lamps and lighting the way for women who used to live in energy poverty.

And how drones are delivering antivenin and other crucial medicines to the heart of the Peruvian Amazon, and helping in search-and-rescue missions during floods.

And how strategically situated oxygen plants are offering Tanzanian hospitals the supply of oxygen they need to perform C-sections and other crucial surgeries.

And how sturdy paper microscopes are offering a high-tech, low-cost way for kids everywhere to not only learn about science, but to do science.

And how we can push back against fake news on the internet to find the truth, and pass it on.

SwitchPoint pushed the door open for more ideas and creators this year than ever before. Let’s leave it open and see what happens.

Don't miss SwitchPoint 2018: Day 1 and join the conversation: @SwitchPointIdea @intrahealth #SwitchPoint

Want to know what happened last year at SwitchPoint? Check it out:

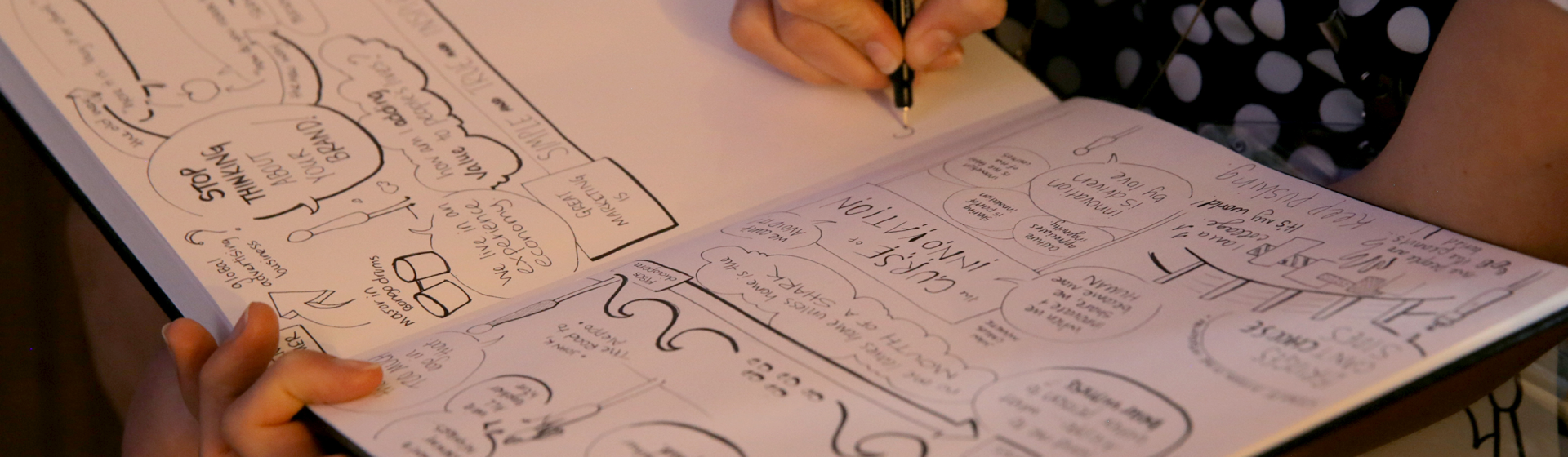

Attendees at Friday's Hone Your Story microlab learned to craft authentic, compelling stories by tapping into their personal repertoire of voice, perspective, and view. Photo by David Nelson for IntraHealth International.

SwitchPointers got their hands on the future at the SwitchPoint Maker microlab. Photo by David Nelson for IntraHealth International.

What does the ideal village look like? And how can it provide the best possible services to residents? These were the questions at Friday's Village People microlab. Photo by David Nelson for IntraHealth International.

Photo by David Nelson for IntraHealth International.

Elena Arguelles (right) and Juan Bergelund (second from right) led the Drone Scavenger Hunt microlab, showing us how robotics and AI can be part the solution to humanitarian problems. Photo by David Nelson for IntraHealth International.

Attendees saw firsthand some of the challenges Peru Flying Labs face as they deliver blood and medicine in the Amazon, conduct search-and-rescue operations after floods, and work to reduce Zika. Photo by David Nelson for IntraHealth International.

At the Follow the Money microlab, an expert panel talked impact investing, corporate partnerships, new funding mechanisms, and more. Photo by David Nelson for IntraHealth International.

Get the latest updates from the blog and eNews