Where We Work

See our interactive map

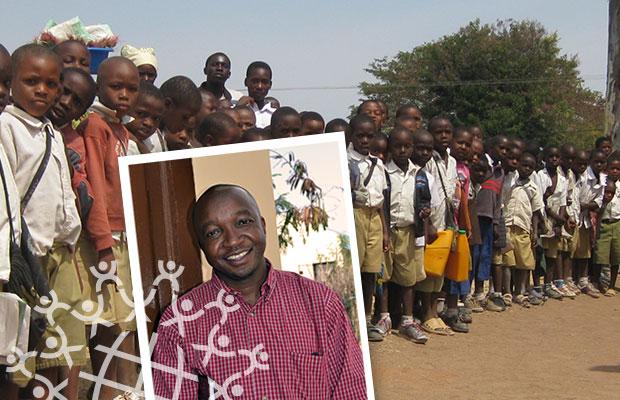

Paul Mwakipesile is the male circumcision program manager for IntraHealth International's Tanzania HIV Prevention Project in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. He is a 39-year-old clinical officer—a position akin to a physician’s assistant.

Q: Did you have sex education or reproductive health education when you were in high school? A: No. By then, HIV/AIDS awareness was still very low, so there was not sex education about condoms or reproductive health. Maybe there was part of a biology course that dealt with the reproductive system—to biologically understand ovulation and pregnancy. But we were not given the life skills for sex-related issues. You had to study that in university and college.

So what has changed for young people since your time as a high school student? Knowledge is more widespread today. Advocacy and information about HIV/AIDS are now going to the villages and to the schools. Schools use strong reproductive health programming for their pupils. We used to think that HIV is only for adults, but now we give the prevention information to these young ones. Boys in form three (grade 3) and form four (grade 4) are very much aware of sexual issues nowadays. They are influenced by TV, magazines, internet, and phones. Now young boys know a lot about HIV/AIDS, sexuality, about love affairs—which was not the case when I was that age. You can call a center to ask about HIV-related programs and they can give you information about HIV/AIDS. In our era, there was no such information. Or you can find youth clubs where they're giving life skills, information on condoms, messages on how to stay faithful, et cetera. Those life skills were not available in the past.

When you were young, did you feel you could seek out health care? No, no, no. Visiting the hospital was a bad experience when I was young, so I was afraid to go to the health care system. And it was unfamiliar because the nature of my parents’ work was not connected with health services. But after studying and being exposed to science, my ambition was to become a doctor, to give good treatment.

What attracted you to IntraHealth’s male circumcision program? I found it to be the only program that can influence a lot of men with HIV/AIDS-related issues. Many men do not participate in health care systems or in HIV/AIDS care. But through male circumcision, we have connected many to the health care system—especially HIV testing and counseling.

It's very difficult to talk about sex as related to other issues and programs, especially in Tanzania, where sexuality is someone talking in silence.

What element of your work do you find most fascinating? The most fascinating part is the community, and how, as a program, we can respond to the community’s demands for our service. When you go to the community, you see that as leaders buy in to the services, they participate in creating demand. The community and its leaders can prevent HIV by taking their own initiative. You find that people are very open and motivated, and they tend to socialize with each other. It is unlike other programs where it's difficult to find people talking openly about HIV/AIDS. When it comes to male circumcision, they talk about it openly. Leaders will say, "You mothers, bring your husbands for male circumcision." It's very difficult to talk about sex as related to other issues and programs, especially in Tanzania, where sexuality is someone talking in silence.

Do you think you’ll continue to work in male circumcision programs? The community’s demand is still high. There is still a lot to do in research, documenting best practice. I see years of work for me to do.

And how does your family feel about your career? They're happy, but they're sometimes worried that I spend a lot of time in the field. But that’s the nature of the work. I have to be in the field to coordinate events, to work with the government health care providers and private ones. There's logistic support, demand creation, and I have to check the data quality. So a lot of the time I've got to travel. But they're happy that I'm doing something for the community. My family does value my career a lot. They are well informed.

Paul has a reproductive health diploma from Liverpool University and a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Open University of Tanzania. He’s earning a master’s in public health through a distance learning program from the London School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

Get the latest updates from the blog and eNews