Where We Work

See our interactive map

Frontline Health Workers Coalition director Vince Blaser asks panelists a question at the ministerial session on health workforce at the Global Conference on Primary Health Care in Astana, Kazakhstan. Photo courtesy IntraHealth International.

These three factors will be critical.

Fellow delegates to last week’s Global Conference on Primary Health Care in Astana, Kazakhstan, have flown home to an awesome yet daunting challenge: 40 years after the landmark Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978 declaring health as a human right, how can we finally make the declaration’s vision of primary health care (PHC) for all a reality?

The monumental 1978 conference in Alma-Ata, USSR (now Almaty, Kazakhstan), pronounced for the first time global agreement that health is a “fundamental human right” and called for “urgent and effective national and international action to develop and implement primary health care throughout the world.”

We’ve come a long way, but are far from reaching the dream.

Representatives from 134 countries broke across political and ideological differences, personally urged on by the likes of the late US Senator Ted Kennedy, and set a target to achieve PHC for all by 2000.

Forty years later we’ve come a long way, but are far from reaching the dream hatched in Alma-Ata.

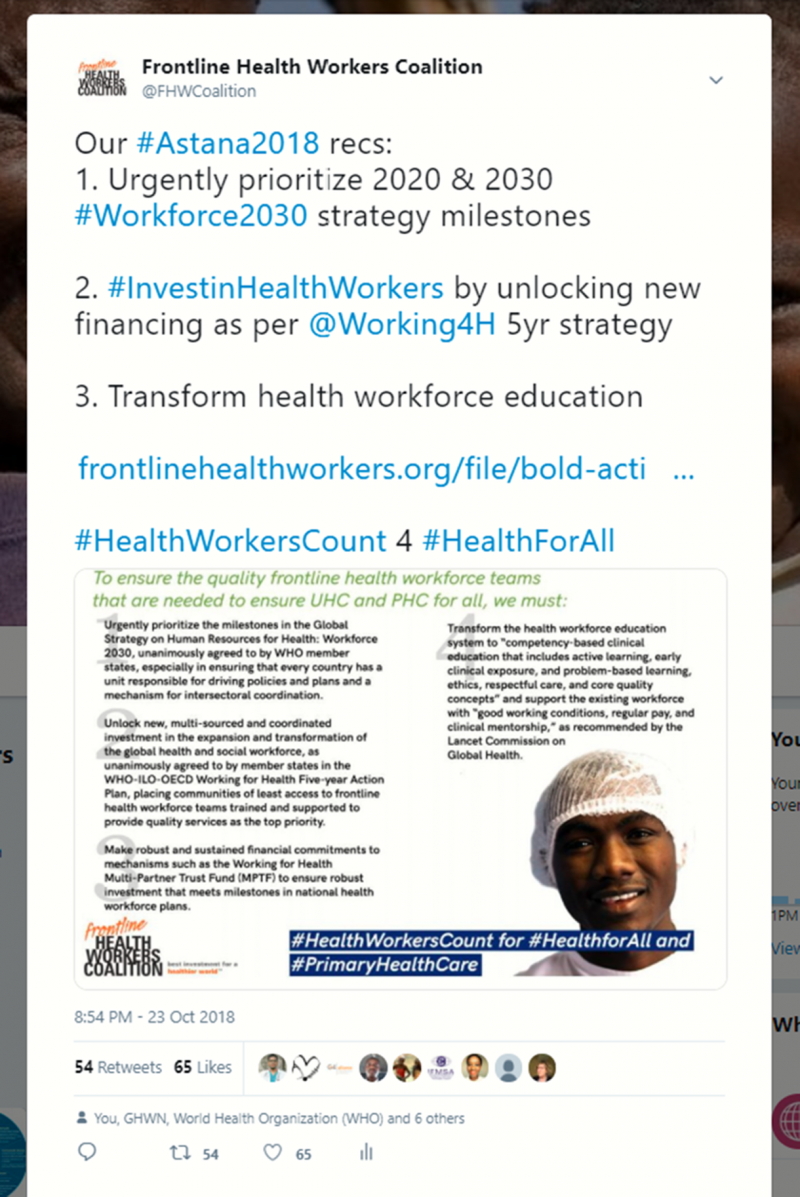

Last Thursday, 1,200 delegates from more than 120 countries renewed the commitment to PHC for all with the Astana Declaration. More than 180 civil society organizations, including the Frontline Health Workers Coalition, through the UHC2030 Civil Society Engagement Mechanism signalled our intent to see PHC for all finally realized and what it will take to get us there.

Here are three factors I believe will be critical to achieving the Astana Declaration.

The evidence and political will behind the Millennium Development Goals and major annual increases in development assistance for health in the 2000s gave rise to progress on many of the top issues in public health: annual deaths of children under 5 more than cut in half and maternal deaths nearly cut in half since 1990, almost a 50% decline in annual deaths from HIV since 2005, and and a 62% cut in the malaria deaths rate from 2000-2015.

But as World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus noted in his opening remarks in Astana, progress has not been equitable. The people whose lives have been saved and made healthier have largely been the easiest to reach.

Following the Alma-Ata Declaration, many countries took action to increase access to PHC, including efforts to usher in community health worker (CHW) programs focused on the areas of least access. Unfortunately, large-scale CHW programs of the 1980s and 1990s largely failed due to a variety of factors, according to leading scholars like Henry Perry of Johns Hopkins University.

Last Friday, the WHO released its first-ever guidelines to optimize CHW programs.

But now many countries, global initiatives, and donors are looking to scale up CHW programs to address the gaps in primary health care access.

Last Friday in Astana, the WHO released its first-ever guidelines to optimize the effectiveness of CHW programs. In the last two decades, CHW programs of all shapes and sizes have been tried and researched, many of which have been supported in some way by the US and other development assistance donors and implemented or supported members of the Frontline Health Workers Coalition.

This evidence has been put to use in some countries’ development of CHW programs—but the release of these guidelines, backed by this evidence, will provide adaptable recommendations for all countries to utilize.

Central to the success of CHW programs, according to the guidelines, will be how well they are integrated into the health system, especially national health workforce plans.

The message that permeated several panels in Astana, made clear by frontline health workers like Maria Valenzuela, Munashe Nyika, and Ruth Tarr, was that teams of well-supported frontline health workers with the education, training, equipment, information, and support they need, are required to deliver PHC for all.

A major factor in the progress made in global health was the solidarity, leadership, and leverage that came with the average annual increase of more than 10% in development assistance for health from 2000-2010. Unfortunately, that assistance has levelled off, averaging a 1% increase since 2010 and decreasing slightly from 2016 to 2017, according to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

At the same time, average domestic spending on health in low-income countries decreased from 1.69% of GDP in 2006 to 1.44% in 2015, according to Save the Children.

While overall global spending on health continues to grow, investment has not been focused on providing quality primary care to communities of least access and, as a result, health inequities are exacerbated. The new report of the Lancet Global Health Commission on High Quality Health Systems in the SDG Era found over 8 million people die annually in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) because of “inadequate access to quality care,” resulting in $6 trillion in economic losses.

The laudable goal of quality PHC for all set forth in the Astana Declaration cannot be achieved without far greater global solidarity to focus and invest in communities of least access to quality health services in LMICs. This means greater investment in these communities by development assistance donors, greater investment by LMICs themselves in PHC, and greater investment from the philanthropic and private sector, especially in the areas where long-term investment is most needed, such as health workforce education and addressing gender inequities.

Although the Astana Declaration lays out the solidarity of commitment to the right of health for all enshrined in the Alma-Ata Declaration and the desire to achieve it, the specific commitments needed to make this vision a reality were as absent last week as they were in 1978.

Thankfully, the framework for what needs to be achieved is there on paper, waiting for bold, sustained action to be taken.

The goal of achieving universal health coverage, or UHC, unanimously agreed to by United Nations member states in 2012, has itself become a driving force for achieving health for all. The opportunity is ripe for concrete commitments to realize the Astana Declaration at the UN High-Level Meeting on UHC in September 2019 in New York.

In the arena of health workforce, where the Frontline Health Worker Coalition focuses our advocacy, the blueprint of what must be committed to next year in New York needs better data to deliver better investment.

The coalition's recommendations are clear: we will need a heavy dose of political will in the form of bold new financial and programmatic commitments, as will other core components of PHC and UHC.

Last week we celebrated the vision for PHC for all enshrined in the Alma-Ata Declaration 40 years ago but lamented our failure to reach its vision. Forty years from today, I hope we celebrate this week in Astana as the starting point for bold actions that made that vision a reality.

This post originally appeared on the Frontline Health Workers Coalition blog.